The Freight Economy Is Showing Signs Of Normalization. But That Does Not Signal A Recession.

While transport capacity has relatively loosened, warehouse utilization remains high, even as consumer retail demand continues to hold well above pre-pandemic levels

A hearty welcome to the 59th edition of The Logistics Rundown, a weekly digest that aims to put some perspective on what’s brewing within the logistics industry. This is a space where we religiously dissect market trends, chat with industry thought leaders, highlight supply chain innovation, celebrate startups, and share news nuggets.

This week, the US witnessed yet another headwind to freight operations as category 4 cyclone Ian made landfall in Florida, battering the Gulf Coast and disrupting life and movement. Coincidentally, cyclone Ian is right in time to flag off Q4 '22 — a peak season quarter showing promise to be as eventful as the one from last year.

A couple of weeks ago, I wrote on how retailers might relive the nightmare from last year. There’s a lot more to uncover on this peak shipping season, and so here’s another edition of the newsletter attempting to make more sense of where the industry is heading.

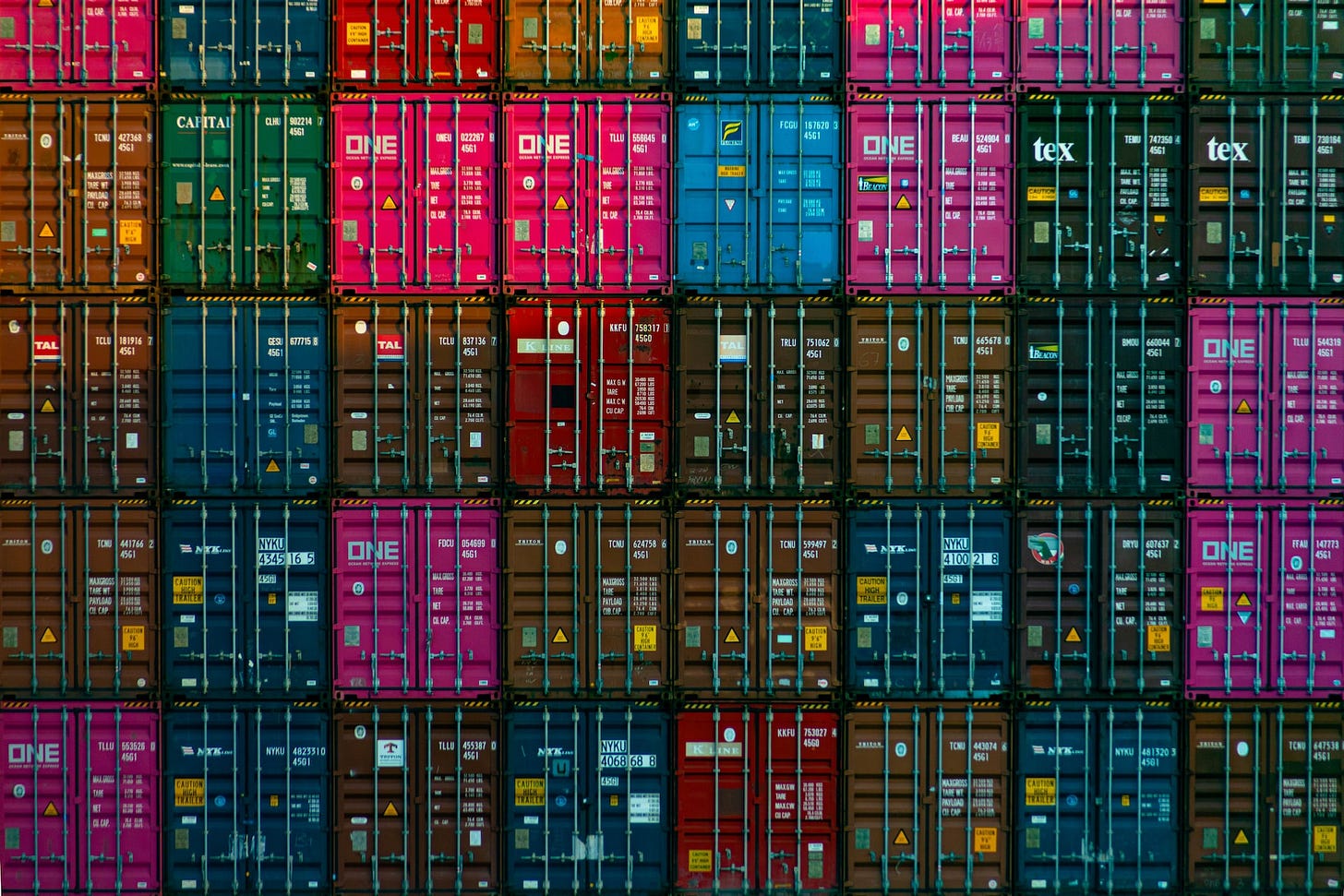

Maritime freight prices continue to drop precipitously across major trade lanes due to lower demand, and container liners are trying everything they can to find a bottom to this slide. They've attempted blank sails over the last few months but will now resort to suspending entire services — as is the case with MSC, which is all set to suspend some services across the trans-Pacific due to a drastic fall in demand.

Despite this, prices continue to sink. A part of this can be attributed to shippers and retailers, who, in an attempt to beat peak shipping queues, ended up shipping inventories much ahead of time. This meant most of these import volumes have reached the US or are in transit already, leading to this 'drop' in import volumes during the actual peak season.

This is reflected in how warehouse capacity is incredibly hard to come by today. Retail inventory levels in the US have continued to grow — vacancy rates for commercial real estate major Prologis' in their top 30 US markets stand below 3%. As a rule of thumb, when vacancy rates fall below 10%, it can be understood that throughput efficiency takes a hit. Workers struggle to move freight around on the warehousing floor when it's overflowing with inventories, naturally impacting their work efficiency.

Retail inventory levels in the US have continued to grow — vacancy rates for commercial real estate major Prologis' in their top 30 US markets stand below 3%.

Lack of warehousing space resulted in drivers unloading containers outside their gates. FRED data on retailers' inventories show a meteoric increase in value of inventories from Oct '21 — a trend that continues till date, with a peak not in sight yet.

The Logistics Managers' Index (LMI) saw inventory levels register 67.6 on its index in August, a reduction of 1.3 from July. Being a diffusion index, an LMI score of more than 50 would reflect growth. At 67.6, the growth of inventory levels is undoubtedly very high, albeit lesser than the all-time high of 80.2 the metric saw in Feb '22.

This is a sticky situation for retailers, considering consumer demand seems to be shifting from durable goods to services, making it harder for them to sell off products bloating their inventories. Bloated inventories are a triple whammy as they increase holding costs, hinder retailer attempts to stock products in demand over the forthcoming holiday season, and reduce available capital (an added nuisance in a climate of increasing interest rates).

Bloated inventories are a triple whammy as they increase holding costs, hinder retailer attempts to stock products in demand over the forthcoming holiday season, and reduce available capital.

"Inflation is also causing the consumption shift as people spend more on necessities now. We are seeing retail market demand normalize, but inventories that have already been bought need to go somewhere," said Ashley McMillan, senior sales manager at Denim.

Interestingly enough, while warehousing capacity is hard to come by, trucking capacity has grown quite a lot in the last few months. LMI published the spread between warehousing capacity and transportation capacity, which really puts things in perspective.

It can be noted that the spread between these capacity metrics we see today has occurred twice since 2019, and they’ve proceeded to close the gap in both the instances. Currently, trucking capacity expansion is still visible. While the rate of growth is expectedly falling, the EIN applications processed in the transportation segment continue to stay elevated compared to pre-pandemic levels.

"There's a flood of capacity in the market, especially with many owner-operators coming in," said McMillan. "This caused rates to bottom out — we have less tender volumes, production is starting to slow down. Many of them can't sustain operations as there's not enough freight to keep all of them in business. Many will start parking their trucks after this peak season or return to working for larger carriers."

With the housing market and manufacturing activity staying stronger than retail demand, flatbed trucking has had better fortunes than dry van over this year. However, with increasing interest rates, McMillan felt this might not be the case going forward.

With the housing market and manufacturing activity staying stronger than retail demand, flatbed trucking has had better fortunes than dry van over this year.

"Flatbed is probably the most stable market in the trucking business, and flatbed drivers are really strategic. They aren't going to face the same pressure that dry van is facing, but we might start seeing flatbed volumes decline over the winter," said McMillan.

With the uncertainties surrounding the peak season, trucking carriers must understand the environment they haul in, considering operational costs are still much higher than pre-pandemic, with higher delays and detention times.

"It's imperative for freight companies to focus their attention on customer relationships and monitor the type of freight they haul — like household goods, food and beverages, and essential retail. These are segments that have consistent demand through the year and are things that can keep their business afloat," said McMillan. "They might not be the most favorable loads to haul as they're not expensive commodities, but these are segments that are key to keeping your business afloat in a climate of low tender volumes."

Even with all the headwinds to operations, the bottlenecks have significantly cooled down for the freight economy at large, evident from a loosening trucking (and maritime) market. Warehousing capacity continues to be an issue, but the situation is quite an improvement from last year. Case in point, capacity utilization has decreased year-over-year, despite retail inventory levels climbing much higher year-over-year.

In essence, while these are unmistakable signs of the market cooling, they are just that — the market continues to normalize and is not showing signs of it heading towards a recession.

The Weekly Roundup

Supply chain shortages are becoming all too common lately, but now it’s starting to hit a little too close to home. A shortage in CO2 production could cause production issues for beer and frozen foods. The American Brewers Association cites high demand and routine maintenance shutdowns of CO2 plants as the culprit.

The US trucking industry is beginning to feel the drop in consumer demand. While the summer season maintained rates and demand, due in large to retailers attempting to shed excess inventory, industry analysts are expecting a muted peak season and weak demand lasting into next year. Shippers are using this as an opportunity to restructure and optimize their supply chain.

The national average for diesel fuel continues its slow decline, and is now averaging $4.889 per gallon. This marks four consecutive weeks of decline in price and marks a continuing downtrend of fuel prices. At this time last year, diesel prices were up $1.483 per gallon.

Major carriers UPS, FedEX, and USPS have had to suspend operations in the wake of hurricane Ian. The category 4 hurricane has caused significant damage and flooding, being rated as the fifth worst storm in US history. The UPS website listed some 800 zip codes that could not be serviced due to damage and safety concerns.

…said who?

“It’s basically a 500-year flood event.”

- Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis, while describing hurricane Ian’s devastation on the state of Florida

Want to talk with us? Have something you'd like us to cover? Drop your thoughts to vishnu@truckx.com

We are TruckX, the Internet of Things plug to logistics. Check us out at www.TruckX.com